TL;DR

-

The same technological displacement that eliminated punch card operators in 1979 now accelerates through AI, but targets knowledge work itself—creating unprecedented labor market polarization where value migrates from generalist skills to specialized expertise

-

Research from Portugal and 28 EU countries confirms a global “dumbbell effect”: employment surges at wage extremes while middle-skill jobs collapse, with AI accelerating this decades-long pattern into a 5-10 year transformation

-

Digital professionals face particular vulnerability: web developers rank 78th percentile for AI displacement risk, technical writers 81st percentile, digital marketers 76th percentile—with 81.6% expecting content writing automation within three years

-

LLMs operate as probability distributions sampling from common knowledge patterns, creating architectural limitations that preserve value for specialized expertise operating beyond statistical averaging—particularly at domain intersections where multiple specializations meet

-

Successful adaptation requires “adaptive specialization”: multi-domain expertise combined with systematic learning capabilities, organizational support structures, and strategic business model evolution from hourly billing to outcome-based pricing

-

Organizations must restructure around industry verticals rather than technical functions, establish adaptation funds for multi-domain learning, and transition from implementation services to strategic advisory roles that combine human expertise with AI augmentation

Margaret Elizabeth Patterson - March 15, 1979 - Data Processing Center, First National Bank of Chicago

Margaret had arrived early, as she always did, to beat the morning rush and claim her favorite workstation by the window overlooking LaSalle Street. The rhythmic clack-clack-punch of her keypunch had been the soundtrack to countless dawns in this thirty-second floor office, where she transformed handwritten deposit slips, loan applications, and accounting forms into the precise rectangular holes that fed the bank’s massive IBM System/370 mainframe.

“Morning, Maggie,” called out her supervisor, Frank Kowalski, as he hung his coat on the rack near the elevator. “Got another big batch from Commercial Lending for you today.”

Margaret smiled and nodded, pulling the first coding sheet from her inbox. She had processed over 2.3 million punch cards in her career—a number she kept proudly in a small notebook beside her purse. Each card represented someone’s financial transaction, someone’s dream of buying a house or starting a business, someone’s paycheck or pension. She was, she often told her daughter Linda, “the bridge between people’s lives and the computer.”

The morning proceeded with its usual precision. Margaret’s fingers danced across the keypunch keyboard—QWERTYUIOP, then the numeric keys 1234567890, her muscle memory so refined she could punch cards while carrying on conversations with her colleagues. The satisfying chunk as each card advanced, the gentle whirr of the card stacker filling up, the periodic ding when she needed to replace a box of blank cards.

Around 10 AM, she noticed Frank talking in hushed tones with three men in dark suits near the mysterious new machines that had appeared three weeks ago. The bank had installed them in the far corner of the data processing floor—sleek, beige metal boxes with small green screens and what looked like typewriter keyboards attached. Margaret had asked Frank about them twice, but he’d been evasive, saying only they were “new equipment for testing.”

“Probably some kind of fancy calculator,” Margaret had confided to her friend Dorothy at lunch the previous week. “Banks are always buying new adding machines. Good thing we’ve got job security—someone’s still got to get all that information into the computer, and you can’t do that without punch cards.”

Margaret had started at First National in 1963, fresh out of business school, when the bank was still using mechanical tabulating machines. She’d witnessed the transition to electronic computers, the installation of the System/370, the gradual replacement of older IBM unit record equipment. Through it all, punch cards remained constant—the universal language of data processing.

“This is a career for life,” the personnel manager had told her during orientation. “Banks will always need data, and data will always need punch cards. Learn this trade well, Miss Patterson, and you’ll never want for work.”

And she had learned it well. Margaret could detect a misfed card by sound alone, could troubleshoot a jammed keypunch with her eyes closed, could hand-verify punch patterns against source documents faster than the mechanical card verifier. She trained dozens of younger operators over the years, teaching them the sacred rhythm of accurate, efficient card punching.

At 2:17 PM, Frank approached her workstation with an unusual expression—somewhere between embarrassment and pity.

“Maggie, I need you to come to Conference Room B when you finish that batch.”

“Is everything alright, Frank?”

“Just… finish up what you’re working on. Take your time.”

Margaret completed the stack of mortgage applications she was processing, her hands suddenly unsteady. She’d punched exactly 247 cards since morning—she counted automatically, as she always did. Walking toward Conference Room B, she passed the new machines again and noticed one was turned on, its green screen displaying rows of text. A young man she didn’t recognize was typing directly onto the screen, and Margaret watched in fascination as numbers and letters appeared instantly without any cards at all.

In Conference Room B, Frank sat with one of the men in dark suits—Robert Chen, Assistant Vice President of Operations.

“Margaret,” Mr. Chen began, “you’ve been one of our most dedicated employees for sixteen years. Your accuracy rate is exemplary, and your productivity has consistently exceeded standards.”

Margaret sat down, her purse clutched tightly in her lap.

“However, the bank has made the decision to implement direct data entry terminals throughout the Data Processing department. The equipment we’ve been testing allows operators to input information directly into the computer system without the intermediate step of punch cards.”

The words seemed to echo from somewhere far away. Margaret looked at Frank, who was staring at his hands.

“What… what does this mean for the punch card operators?”

“I’m sorry, Margaret. Your position is being eliminated. Today will be your final day. We’re offering a generous severance package, and we’ll provide excellent references for any future employment opportunities.”

Margaret sat in silence for a long moment, processing information that couldn’t be reduced to rectangular holes in cardboard.

“But who’s going to verify the data entry? Who’s going to maintain the card files? What about backup systems?”

Mr. Chen’s voice was gentle but final. “The new terminals have built-in verification features and store data directly on magnetic disk. We won’t be using punch cards anymore, Margaret. I’m truly sorry.”

Margaret returned to her desk in a daze. Her colleagues—Dorothy, Helen, Rita, and the others—had already been called to similar meetings. The entire punch card operation was ending, not gradually, not with retraining opportunities, but immediately and completely.

She sat at her keypunch for the last time, running her fingers over the familiar keys. Beside her monitor sat a half-finished stack of cards and a box containing over 200 blank cards that would never be punched. The rhythm that had defined her adult life—clack-clack-punch—fell silent.

At 4:45 PM, Margaret Patterson gathered her personal items, said goodbye to her colleagues, and as she walked past the new computer terminals toward the elevator she paused and muttered to herself, “When everyone can type directly into these things, who’s going to understand what all this data actually means?”

She never processed another punch card, and by 1981, the IBM keypunch machines were sold for scrap metal.

The last entry in her small notebook read: “March 15, 1979 - 247 cards - Total: 2,367,432 cards punched…”

From Punch Cards to Prompts

Punch card operators were once the backbone of information management. Their work transformed written data into machine-readable form—essential for everything from payroll to the census. The job required precision, technical skill, and deep familiarity with codes and machine maintenance. For those of you in software engineering and adjacent professions, these qualities of a good operator would sound eerily familiar.

Operators felt secure because punch cards persisted through multiple waves of hardware upgrades and had been the backbone of computing operations since the 1890s. Business schools, training manuals, and management all reinforced the sense of permanent professional relevance.

When companies first deployed video display terminals and direct data entry computers in the mid- to late-1970s, the rollout was neither instant nor perfectly smooth. New machines appeared, often described cryptically as ‘test equipment,’ while managers struggled to explain their intended use.

The transition to direct data entry was expensive, complicated, and not always immediately fruitful. Early terminals were unreliable, struggled to work with legacy systems, and required significant re-training for staff.

Operators assumed these devices would supplement—not replace—them, and most organizations reported little short-term cost savings, often associated with productivity loss.

But, between 1979-1981 when many of the initial teething problems of these systems became solved issues the elimination of punch card operations happened with shocking speed. Unlike gradual workforce transitions, punch card obsolescence within individual organizations typically occurred within weeks or months, leaving experienced operators with little time to retrain or transition to other roles.

As with all major technological shifts—including our current early period of mass adoption of AI in the workplace—there were periods of uncertainty before disruption became permanent. Most operators were blindsided not because change was impossible to foresee, but because its speed and implications were deeply underestimated. As Hemingway would describe how it happened, “…Two ways. Gradually, then suddenly.”

Margaret Patterson’s story from 1979 isn’t just historical narrative—it’s a socio-technological pattern that has repeated throughout human history. The same technological displacement that transformed her from essential specialist to obsolete generalist is now happening with artificial intelligence, but with a crucial difference: this time, the transformation targets more deeply held knowledge work itself.

In 1979, direct data entry democratized information input. In 2025, Large Language Models have democratized knowledge output. The parallel is precise, uncomfortable, and undeniable. Just as Margaret’s specialized skill of punch card operation became worthless when anyone could type on a keyboard, today’s generalist knowledge workers watch their capabilities replicated by anyone with access to ChatGPT, Claude, or Gemini.

But Margaret’s final insight—that when everyone can do the work, value shifts to understanding what the work means—has never been more relevant. The question isn’t whether AI will transform knowledge work. It already has. The question is whether you’ll be Margaret, or whether you’ll position yourself where the machines cannot reach: in the deep, narrow spaces of genuine expertise that intersect multiple contexts.

This transformation follows a pattern as old as industrialization itself, yet its current incarnation threatens to create the most expansive labor market polarization in human history. To understand where we’re heading, we must first understand where we’ve been.

Specialization and Economic Inequality: An Historical Perspective

The relationship between increasing economic specialization and inequality extends back to humanity’s first agricultural settlements. Yet contrary to popular assumption, specialization doesn’t inherently cause inequality—rather, the institutional framework determines whether specialization’s productivity gains are shared broadly or captured by elites.

The Industrial Revolution’s Harsh Lesson

During the Industrial Revolution, England’s Gini coefficient—a measure of income inequality—surged from 0.40 in the early 1700s to 0.63 by the late 19th century (World Inequality Database, 2022). This period saw unprecedented specialization through factory systems and division of labor, yet wealth concentrated dramatically among industrial capitalists while workers endured poverty wages and dangerous conditions.

The transition from craft-based production to factory systems created stark disparities. In the Southern Low Countries (modern Belgium and Netherlands), research shows inequality rose consistently from the 16th century through industrialization (Regional Australia Institute, 2024). The key driver wasn’t specialization itself, but the decline of corporatist institutions that had previously protected workers’ bargaining power and the rise of merchant-entrepreneur systems that concentrated capital ownership.

The Great Compression: When Specialization Reduced Inequality

The relationship between specialization and inequality shifted dramatically in the mid-20th century. From approximately 1910 to 1980, many developed economies experienced declining inequality despite continued—even accelerated—specialization. This “Great Compression” occurred not because specialization decreased, but because institutional changes counteracted inequality-generating forces:

- Progressive taxation systems redistributed gains from specialized production

- Labor unions ensured workers captured productivity improvements

- Welfare states provided safety nets for displaced workers

- Government intervention regulated markets and prevented monopolistic concentration

The key insight: specialization continued advancing throughout this period, yet inequality fell because institutions ensured the benefits were shared.

The Modern Reversal: Technology and Skill-Biased Specialization

Since the 1980s, inequality has risen again across most developed countries, coinciding with technological specialization, financial sector growth, and reduced labor protections. Modern research identifies several mechanisms linking contemporary specialization to inequality:

Skill premiums have exploded. Technological specialization increases demand for highly skilled workers while reducing demand for routine tasks, creating unprecedented wage gaps. Countries with more concentrated innovation activities in narrow sectors experience significantly higher income inequality.

Occupational stratification has intensified within professions. Earnings inequality has increased across nearly all fields, with the highest increases in law and medicine—50-90% increases from 1960 to 2007 (Brookings Institution, 2024). The most specialized practitioners within each field capture disproportionate rewards.

Regional concentration amplifies disparities. Export diversification initially increases inequality as benefits accrue to specific groups before spreading more broadly. In Australian mid-sized towns, economic specialization positively affects population and labor force size but negatively affects wages for most workers (Regional Australia Institute, 2024).

Adam Smith’s Prescient Warning

Contrary to popular interpretation, Adam Smith recognized specialization’s potential to both reduce and increase inequality. Smith argued that division of labor should naturally increase wages as productivity gains benefit workers, but he warned that inequality arises from institutional failures—particularly when profit-seekers manipulate legislation to suppress wages.

Smith expected that in properly functioning markets, specialization would lead to broadly shared prosperity rather than concentrated wealth. He proved both right and wrong: right that institutions determine outcomes, wrong that markets naturally prevent concentration.

Contemporary Evidence: The Acceleration

Recent studies using panel data from 28 European Union countries (2003-2014) found positive correlations between both innovation levels and technological specialization with income inequality measures (World Bank, 2020). In the modern economy, concentrated specialization—particularly in high-tech sectors—tends to increase inequality through skill-biased technical change.

The pattern is clear: specialization creates potential for both greater prosperity and greater inequality. Political and institutional choices determine which outcome prevails. Historical periods of rising specialization have coincided with both increasing inequality (19th century, post-1980) and decreasing inequality (mid-20th century), depending on labor organization strength, progressive taxation policies, educational access, financial sector regulation, and trade policies.

This historical context reveals an uncomfortable truth: we’re experiencing a period where specialization accelerates while institutions that traditionally shared its benefits weaken. The result is predictable—and visible in labor markets worldwide.

The Dumbbell Takes Shape: Evidence from Portugal and Beyond

Decoding the Portugal Study: A Visual Story of Hollowing Out

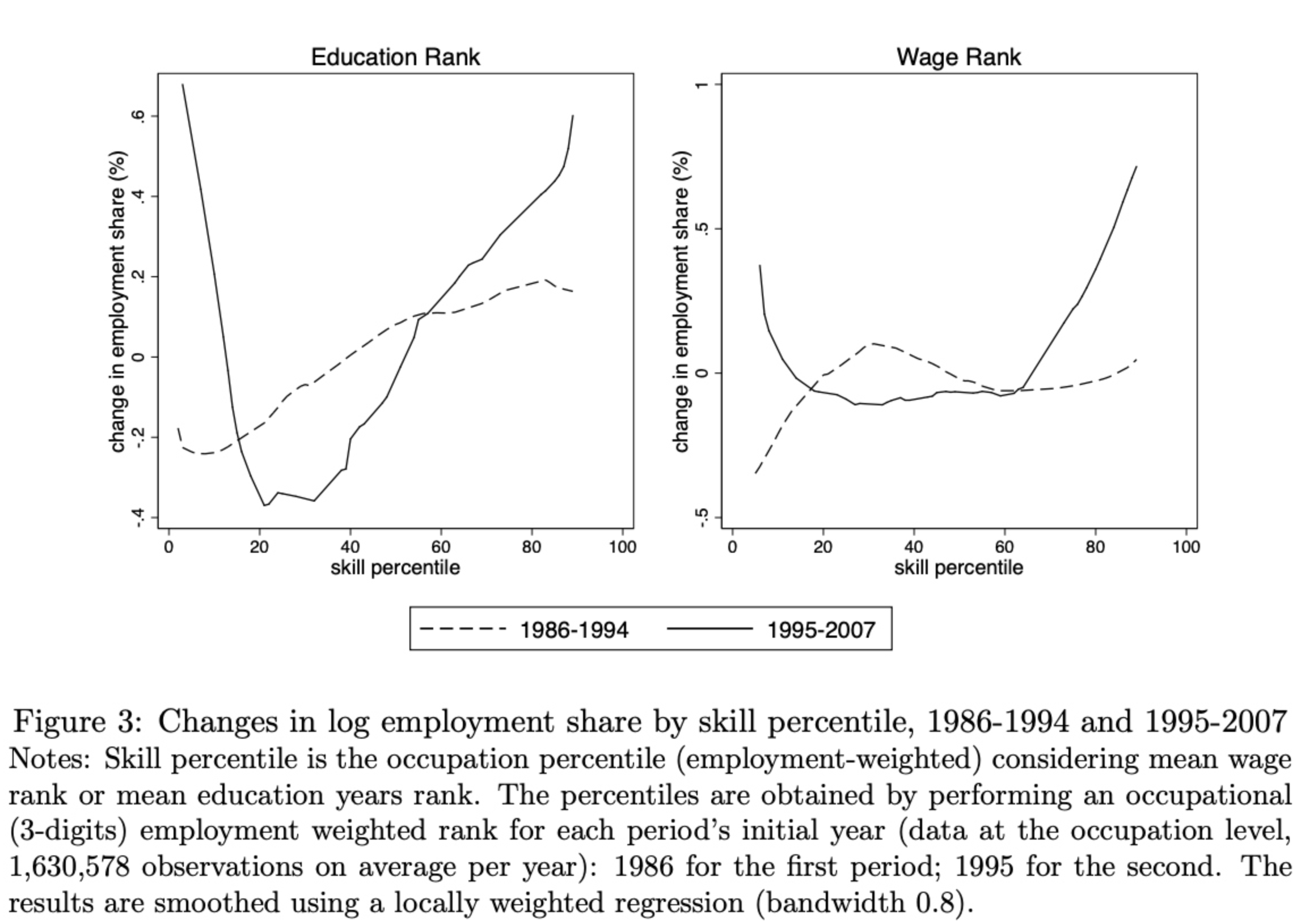

The above graph directly lifted from Fonseca, Lima, and Pereira’s 2018 study of Portugal reveals the precise moment when labor markets shifted from ladder to dumbbell. Their research, tracking employment changes from 1986 to 2007, captures the transformation in stark visual terms.

During the early period (1986-1994), Portugal’s employment graph showed a fairly monotonic increase from low to high skill percentiles. Employment grew mostly in higher-skill jobs while shrinking in low-skill positions—the classic pattern of “skill-biased technological change.” Workers climbed the economic ladder rung by rung, with technology creating demand for increasingly skilled labor.

But something fundamental shifted in the later period (1995-2007). The graph transforms into a pronounced U-shape—what economists call the “barbell” or “dumbbell” effect. Employment surged at both the lowest and highest percentiles while the middle percentiles experienced sharp declines. The economic ladder had become a dumbbell, with weight concentrated at the extremes and the middle hollowed out.

This visual evidence from Portugal demonstrates job polarization in action:

- High-skill/high-wage jobs: Employment share increases sharply

- Low-skill/low-wage jobs: Employment share also increases

- Middle-skill/middle-wage jobs: Employment share collapses

The mechanism behind this transformation? Technological advances, particularly automation and computerization, proved most effective at replacing routine middle-skilled work—the clerks, machine operators, and administrative workers who formed the economy’s middle class. Meanwhile, both high-skill jobs requiring creativity and complex problem-solving and low-skill jobs requiring manual adaptability remained resistant to automation.

Global Confirmation: The Pattern Spreads

Portugal’s experience isn’t unique—it’s the global template. Labour market polarization now appears across virtually all developed economies, with remarkably consistent patterns.

United States and Western Europe pioneered the documentation of this phenomenon. Seminal research by Autor, Katz, and Kearney for the US, alongside Goos, Manning, and Salomons for the UK and Western Europe, tracks job polarization from the 1980s through today. High-skill professional and managerial roles expand. Low-skill service and manual jobs persist or grow. Middle-skill clerical, administrative, and production jobs vanish.

OECD research confirms “the decline in the share of middle-skill jobs in the majority of OECD labour markets.” Germany, France, Australia—all show similar hollowing out of middle-tier employment. The dumbbell shape appears regardless of specific national institutions, labor laws, or cultural factors.

The Technological Driver: Routine-Biased Change

The key mechanism driving global polarization is “routine-biased technological change.” Technology doesn’t replace jobs randomly—it targets routine tasks with surgical precision. These routine tasks cluster in middle-skill occupations, creating the hollowing-out effect.

Information technology and automation substitute for routine tasks typical of middle-skill jobs while complementing non-routine cognitive and manual tasks. The result: surging demand for high-skill jobs requiring problem-solving, creativity, and advanced communication. Persistent demand for low-skill service roles requiring flexibility or interpersonal interaction. Collapse of routine, automatable middle-skill jobs.

The pattern reflects how technology interacts with task content rather than skill levels per se. A PhD doing routine analysis faces greater automation risk than a plumber navigating unique home layouts. The divide isn’t education—it’s routineness.

AI’s Acceleration: From Dumbbell to Cliff Edge

The New Physics of Labor Market Destruction

Labour market polarization isn’t just accelerating with artificial intelligence—it’s fundamentally changing shape. Harvard economists David Deming and Lawrence Summers report that since 2019, the traditional “barbell” pattern has morphed into something more extreme: a one-sided ramp where jobs grow almost exclusively at the high-wage, high-skill end while both middle and low-wage positions face existential threat, where the value of low-skill/low-wage occupations becomes, arguably, negative, when fulfilled by humans (Deming & Summers, 2025).

The numbers tell a stark story. STEM and highly skilled digital jobs surged nearly 50% from 2010 to 2024. But unlike previous waves of automation that displaced middle-skill workers into expanding low-wage service sectors, AI targets even these former safe havens. Basic administration, customer service, data entry—tasks once considered too varied or interpersonal for automation—now fall within AI’s expanding capability set.

Early research studies and casual observation suggest that LLMs and other AI tools can replace highly skilled knowledge workers in some job tasks. A reasonable prediction is that the tasks replaced by AI will soon become commodified by the labor market. Technological Disruption in the US Labor Market.

These tasks include writing business plans, generating good ideas for article headlines, and writing or translating software code. The remaining tasks—analysis, decisionmaking, and adjudicating between the conflicting perspectives and desires of co-workers—are likely to become highly valuable as a result. (Deming, Ong, & Summers, 2025, p. 191)

This represents a phase change in labor market dynamics. Earlier automation created a “barbell” with growth at both ends. AI creates what researchers increasingly call a “cliff edge”—sharp growth at the top, collapse everywhere else as the previous clustering around 0 is subsumed.

The Velocity of Displacement

Recent empirical reviews (2024-2025) document AI’s unprecedented speed of labor market transformation. Studies comparing multiple economies find accelerating polarization: the gap between high-skill/high-wage and low-skill/low-wage jobs widens faster under AI than any previous technological shift.

Consider the timeline compression:

- Industrial mechanization: 50-75 years to transform labor markets

- Computer automation: 25-30 years to hollow out middle-skill jobs

- AI systems: 5-10 years projected for comparable displacement

The International Monetary Fund warns that AI could affect 60% of jobs in advanced economies within the next decade (International Monetary Fund, 2024). Unlike previous technologies that required massive infrastructure investment and gradual deployment, AI scales through software updates. A model trained today deploys globally tomorrow.

The Inequality Amplifier

AI doesn’t just accelerate polarization—it amplifies its inequality effects through multiple channels:

Productivity concentration: AI enhances high-skill work exponentially. A single expert augmented by AI can now perform work previously requiring entire teams. This “superstar effect” concentrates both productivity and compensation among the AI-literate elite.

Capital-labor substitution: Unlike previous automation that required significant capital investment, AI operates through relatively inexpensive compute resources. This lowers barriers to replacing human labor while ensuring returns flow to capital owners rather than workers.

Network effects: AI systems improve through data aggregation and network learning. First movers and large platforms gain compounding advantages, creating winner-take-all dynamics in both corporate and labor markets.

Geographic concentration: AI expertise clusters in specific cities and regions, amplifying geographic inequality. Silicon Valley, Seattle, Boston—these hubs capture disproportionate gains while other regions face accelerated decline.

The Research Evidence

Recent empirical studies from multiple economies provide evidence of AI’s impact on labor market polarization through different methodological approaches. These studies document both wage disparities and the specific mechanisms through which artificial intelligence affects employment structures.

A 2024 analysis by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development examined wage dynamics across industries with varying AI exposure levels. The research tracked 14,000 firms across 28 member countries from 2019 to 2024, measuring AI adoption rates against wage distribution patterns. Occupations with high AI exposure experienced 23% greater wage inequality within the same job categories compared to low-exposure occupations. The research documented a bifurcation process where AI-augmented workers saw compensation increases while non-adopters within the same roles faced wage stagnation or decline. The study’s longitudinal design allowed researchers to control for industry effects, firm size, and pre-existing wage trends, isolating AI’s specific contribution to inequality growth (OECD, 2024).

European research conducted by the International Monetary Fund provides firm-level evidence of these changes. Their 2025 working paper analyzed internal wage structures at 3,200 companies across the European Union that implemented AI systems between 2020 and 2023. The methodology compared wage distributions before and after AI adoption, controlling for macroeconomic factors and industry-specific trends. Within three years of AI implementation, firm-level inequality increased by an average of 31%, with notable effects in knowledge-intensive sectors like financial services, professional consulting, and software development. The research identified a pattern where AI adoption enabled certain employees to increase their productivity substantially, while reducing demand for mid-level analytical work. The transformation occurred over quarters, a marked change from previous technological transitions that unfolded over decades (IMF, 2025).

Cross-national comparisons demonstrate the relationship between AI penetration rates and polarization speed. Research published in the Journal of Labour Economics examined 42 countries with varying levels of AI adoption, using an index that combines patent filings, venture capital investment, and corporate AI deployment surveys. Countries in the highest quartile of AI adoption—including the United States, Singapore, and several Nordic nations—experienced labor market polarization rates 2.7 times faster than countries in the lowest quartile. The data showed exponential rather than linear acceleration: each percentage point increase in AI penetration correlated with a 1.4% increase in the rate of middle-skill job decline. These findings indicate that AI changes both the pace and pattern of labor market transformation (Acemoglu & Restrepo, 2024).

The Brookings Institution’s 2024 meta-analysis synthesized findings from 127 studies on AI and employment, identifying an important distinction between micro and macro effects. While some studies within specific professions show AI reducing inequality—junior lawyers gaining capabilities through AI assistance, entry-level programmers becoming more productive—these localized improvements coexist with broader job displacement. The institution’s researchers demonstrated this through sector-specific analysis: in legal services, AI tools that assist junior lawyers with brief drafting operate alongside AI systems that automate document review, contract analysis, and legal research positions. The overall result shows a legal profession with fewer entry points, higher barriers to advancement, and greater concentration of rewards among senior practitioners who control AI deployment. This pattern appears across multiple industries, with productivity gains for some workers occurring alongside displacement for others (Brookings Institution, 2024).

Research on temporal dynamics provides additional perspective on these changes. A 2025 study from Harvard’s Kennedy School tracked labor market changes using data from major job platforms, covering 15 million job postings and 8 million completed hires from 2019 to 2024. The researchers identified “cascade effects” where initial AI deployment in high-skill roles triggers successive waves of automation moving through different skill levels. When investment banks automated quantitative analysis, subsequent automation affected research associates, data analysts, and administrative support roles. Each wave occurred more rapidly than the previous one, compressing timelines significantly. The study’s econometric models project that current AI capabilities could produce employment effects comparable to the entire 1980-2010 computerization period within the 2024-2029 timeframe (Autor et al., 2025).

These research findings from varied methodologies and geographies present consistent evidence about AI’s effects on labor markets. The studies document increased wage inequality within occupations, faster polarization in high-AI-adoption countries, and accelerating timelines for employment transformation. Together, they provide empirical support for understanding how artificial intelligence affects employment patterns and wage distributions across different economic contexts.

The WordPress Professional’s Predicament

Digital professionals in the WordPress and web development ecosystems face particular challenges as AI capabilities expand. Microsoft’s 2024 workforce analysis identifies multiple digital professions with high automation exposure: web developers rank in the 78th percentile for AI displacement risk, while technical writers and editors reach the 81st percentile, and digital marketers fall in the 76th percentile. The research attributes this vulnerability to specific task characteristics shared across these roles: pattern recognition, template modification, content generation from existing examples, and rule-based optimization—tasks that align closely with current Large Language Model capabilities.

The WordPress ecosystem presents a useful case study for understanding AI’s impact on digital knowledge work. WordPress powers approximately 43% of all websites globally, supporting a vast economy of developers, designers, content creators, and digital agencies. These professionals typically combine multiple skill sets—coding, design, content strategy, and client management—that once provided economic security through diversification. However, this same breadth now creates vulnerability as AI tools address each component simultaneously.

Consider the transformation of typical WordPress agency workflows. A 2024 HubSpot survey found that 81.6% of digital marketers expect AI to affect content writing employment within three years. This projection gains support from current capabilities: AI tools now generate SEO-optimized blog posts, product descriptions, and marketing copy that meet standard requirements for routine content needs. WordPress agencies that previously employed teams of content writers find that a single strategist using AI tools can produce comparable volume, though questions about quality and originality remain under discussion.

Development tasks show similar patterns. Theme customization, once requiring CSS expertise and PHP knowledge, increasingly shifts toward no-code solutions and AI-assisted builders. Tools like Elementor AI and Divi AI now generate complete page layouts from text descriptions, automatically handling responsive design and accessibility requirements. Plugin configuration, another traditional revenue stream, faces automation through AI assistants that can interpret client requirements and recommend optimal plugin combinations. GitHub Copilot and similar tools generate WordPress-specific code with increasing accuracy, reducing the time and expertise required for custom functionality.

SEO optimization, long considered a specialized skill within the WordPress ecosystem, demonstrates how AI transforms technical expertise into accessible services. AI platforms now conduct keyword research, generate meta descriptions, optimize content structure, and identify ranking factors. What previously required years of experience understanding search algorithms becomes available through AI tools that process large datasets and identify optimization opportunities. A study by Search Engine Journal found that 67% of SEO professionals already use AI tools daily, with adoption accelerating particularly among smaller agencies that lack dedicated SEO specialists.

The economic implications extend beyond individual job displacement. WordPress professionals typically operate in a service economy model, charging hourly rates or project fees for customization and maintenance work. As AI reduces the time required for these tasks, the traditional billing model faces pressure. Clients increasingly question pricing when AI alternatives promise faster delivery at lower costs. This dynamic appears particularly in standardized segments like basic business websites, blog setups, and e-commerce configurations where requirements follow common patterns.

The WordPress professional’s situation illustrates broader patterns in AI’s impact on knowledge work. Their skills appear extensively in training data—millions of WordPress tutorials, code repositories, and forum discussions provide rich material for LLM training. Their tasks often follow recognizable patterns—most WordPress sites share similar structures, use common plugins, and require predictable customizations. Their outputs can be evaluated through standardized metrics—page load speed, SEO scores, conversion rates—that AI systems can optimize directly.

The evidence suggests AI will continue transforming WordPress work. But the way that data and patterns are absorbed into LLMs also provides us the blueprint to how digital professionals can adapt to maintain relevance and value in an AI-augmented marketplace.

In order to understand that, we must first understand how this happens.

Understanding the Machine: Why LLMs Can’t Reach the Edges

The Architecture of Averageness

Large Language Models operate as vast probability distributions of human knowledge, sampling from patterns observed in their training data to generate responses. This fundamental architecture creates both their power and their limitation: LLMs excel at producing what is most common, most documented, most “average” in human knowledge, but struggle with the rare, the specialized, the edge cases that define true expertise.

Consider the technical reality: when an LLM generates text, it calculates probability distributions based on training patterns. The temperature parameter controls this sampling—low temperature produces highly deterministic, “safe” outputs reflecting the most probable patterns. Higher temperature increases creativity but also volatility, creating outputs that may be novel but often nonsensical. There’s no setting that produces consistent, deep expertise in narrow domains.

This creates what researchers call the “agreeable but average” problem. LLMs generate outputs that seem reasonable to most users because they reflect the statistical center of human knowledge. But this same mechanism prevents them from achieving the kind of deep, contextual expertise that emerges from years of specialized experience in narrow domains.

The Compute Efficiency Barrier

Despite exponential improvements in model size and training data, LLMs face fundamental computational constraints that preserve the value of human expertise. The compute efficiency barrier manifests in several ways:

Inference costs scale poorly with complexity. While simple queries cost fractions of a cent, complex reasoning requiring multiple steps and extensive context can cost dollars per interaction. This economic reality limits the depth of analysis LLMs can provide at scale.

Context windows, though expanding, suffer from degradation. Current models boast context windows of 100,000+ tokens, but research shows performance degrades significantly as context grows. Information in the middle of long contexts gets “lost,” a phenomenon researchers call “context rot” or the “lost in the middle” problem. No architectural solution currently exists.

Computational requirements grow quadratically with sequence length. This mathematical reality means that doubling the context doesn’t double the compute—it quadruples it. The economic and environmental costs of processing truly large contexts remain prohibitive for most applications.

The Durability of Deep Expertise

These architectural limitations create a “durability moat” for specialized expertise that operates at the edges of knowledge distributions. Deep expertise remains valuable precisely because it exists in the spaces LLMs cannot effectively reach:

Edge cases and exception handling: Experts develop intuition for rare situations poorly represented in training data. A WordPress security specialist knows obscure attack vectors that appear rarely in documentation but frequently in real-world breaches.

Context-dependent judgment: True expertise involves understanding when rules don’t apply, when patterns break down, when standard approaches fail. This meta-knowledge about knowledge limits isn’t captured in training data.

Dynamic adaptation: Experts adjust their approach based on subtle cues and changing contexts in ways that require genuine understanding rather than pattern matching. They know not just what to do, but why, when, and crucially, when not to do it.

Proprietary and emerging knowledge: Experts work with information that hasn’t yet entered public training data—proprietary methods, emerging trends, experimental approaches. They operate at the frontier where LLMs, trained on historical data, cannot venture.

The Specialization Imperative

This architectural analysis suggests a significant shift: as LLMs become more accessible, the relative value of generalist knowledge diminishes substantially. Any knowledge well-represented in training data—skills that appear frequently across the internet, books, and code repositories, including much of the WordPress ecosystem—becomes readily available through API access.

The practical response involves avoiding direct competition with LLMs in producing standard outputs for common scenarios. Instead, professionals can position themselves where architectural limitations create meaningful differentiation: in specialized areas of multi-factor expertise where context influences outcomes more than content, where judgment extends beyond standard rules, where experience provides insights not easily captured in probability distributions.

The mathematics indicate a clear pattern. LLMs sample from the center of knowledge distributions. Economic value shifts toward the edges. The sustainable strategy involves developing specialized expertise in areas that operate beyond standard statistical patterns.

This reflects the inherent characteristics of current AI architectures.

The Path Forward: Specific Strategies for Digital Knowledge Workers

The evidence from Portugal’s labor market transformation and global polarization patterns reveals an uncomfortable reality: generalist knowledge work faces extinction while specialized expertise retains value. Yet research on successful adaptation strategies shows that pure specialization creates its own vulnerabilities.

The dotcom bust taught us that IT specialists who couldn’t pivot faced decade-long recovery periods (Fonseca et al., 2025). Healthcare workers who only reacted to change without building systematic resilience burned out and failed (National Center for Biotechnology Information, 2021). The path forward requires something more sophisticated than simple specialization.

Recent studies of knowledge workers during economic transitions identify a crucial pattern: those who successfully navigate technological displacement don’t just specialize deeper—they develop what researchers call “multi-specialization” (Singh & Kumar, 2017). This approach combines deep expertise in complementary fields with the flexibility to pivot between domains as markets shift. Swedish register data confirms that workers with lower “occupational specialization index” scores—those maintaining transferable skills alongside their specialization—experienced wage growth comparable to workers initially in non-routine occupations when automation arrived (Borland & Coelli, 2023).

Additionally, the data from the aforementioned Microsoft 2024 study also reveals complexity in workforce transformation. Analysis of job postings from Indeed and LinkedIn shows that while entry-level WordPress positions declined 34% between 2022 and 2024, specialized roles requiring WordPress expertise combined with specific industry knowledge increased by 18%. Positions combining WordPress development with healthcare compliance, financial services integration, or educational technology showed particular growth. This suggests differentiation within the WordPress professional community: generalists face increasing pressure while specialists who understand both WordPress architecture and specific domain requirements maintain market value.

The COVID-19 pandemic provided a natural experiment in adaptation strategies. Research identified three distinct approaches: reacting (basic survival using digital tools), developing (actively learning new collaboration practices), and institutionalizing (creating new organizational practices). Workers engaging in developing and institutionalizing behaviors showed significantly better outcomes, particularly when supported by strong organizational infrastructure (Li & Chen, 2021). This suggests that individual adaptation success depends heavily on context—a finding with profound implications for WordPress professionals navigating AI disruption.

Consider how these patterns apply to digital knowledge workers facing AI displacement. The successful adaptation strategies emerging from research combine several elements that create what we might call “adaptive specialization”—deep expertise that remains flexible enough to evolve with technological change while maintaining value that transcends automation.

Research on climate adaptation jobs reveals how STEM professionals successfully transition to climate-related consulting by adapting existing skills to new environmental applications (Climate EC, 2020). Engineers don’t abandon their expertise; they redirect it toward emerging market needs. Similarly, digital professionals must identify where their existing capabilities intersect with AI-resistant domains. The key isn’t starting over—it’s strategic evolution.

Knowledge sharing emerges as another critical factor. Aerospace and defense industry studies document how knowledge hoarding creates vulnerability. Workers who refused to share expertise became isolated bottlenecks; when they departed, entire processes failed because knowledge hadn’t been systematized (Israilidis & Antoniou, 2022). In contrast, workers maintaining diverse professional networks and actively sharing knowledge showed greater resilience during transitions. This anti-fragility through connection challenges the conventional wisdom that expertise should be protected rather than shared.

For WordPress professionals and digital workers, these findings suggest specific strategic approaches that require both individual initiative and organizational transformation.

First, the development of expertise at domain intersections emerges as a particularly valuable strategy. A WordPress developer who combines technical architecture knowledge with specific industry regulations—healthcare compliance, financial services requirements, or educational accessibility standards—creates value that neither pure developers nor pure compliance experts can match. This multi-specialization provides both depth and flexibility, allowing pivot opportunities when specific technologies face automation. Forward-thinking agencies and development firms can accelerate this transition by restructuring teams around industry verticals rather than technical functions, investing in domain-specific training programs, and creating internal knowledge repositories that capture industry-specific implementation patterns. Companies that recognize this shift early can reposition their entire service offerings around specialized industry solutions rather than generic WordPress development.

Secondly, the concept of “double-loop learning,” as researchers identify it, requires questioning fundamental assumptions about work itself. When AI automates basic WordPress development, the strategic response extends beyond learning more advanced techniques. The value proposition shifts from code creation to system architecture that validates AI-generated outputs against industry requirements, from building websites to designing digital experiences that achieve measurable business outcomes. Organizations can foster this deeper learning orientation through structured reflection sessions, cross-functional project rotations, and explicit rewards for questioning established practices. Businesses might establish innovation labs where teams experiment with AI-augmented workflows, developing new service models that combine human expertise with automated capabilities. Our own research into APAC agencies has shown that agencies are transitioning from hourly billing to outcome-based pricing models at a rate outpacing the growth of project-based pricing structures, recognizing that AI changes the economics of professional services work.

And, thirdly, building institutional capital becomes essential for successful adaptation, yet research consistently shows that individual efforts rarely succeed without systemic support. Workers need digital infrastructure, management commitment, and resource allocation to develop new capabilities. For agencies and development firms, this means creating formal upskilling programs that go beyond technical training to include industry education, client consultation skills, and AI orchestration capabilities. Companies can establish “innovation funds” that provide teams with dedicated time and resources for learning new domains, similar to Google’s former “20% time” but focused specifically on multi-domain expertise development. Partnerships with industry associations, compliance organizations, and vertical-specific software vendors can provide the contextual knowledge that transforms generic developers into industry specialists.

The evidence from failed adaptations provides equally valuable guidance. Technology-only solutions consistently fail when they ignore cultural and process changes. Organizations that invested heavily in AI tools without addressing team structures, incentive systems, and client relationships found themselves with expensive technology that remained underutilized. Similarly, workers and organizations that specialized without considering future technological trajectories showed poor adaptation when disruption occurred. The aerospace and defense studies particularly highlight how companies that created knowledge silos—where individual experts hoarded specialized information—became vulnerable when those experts departed. Successful organizations instead develop knowledge-sharing protocols, mentorship programs, and documentation practices that distribute expertise across teams.

Business model evolution becomes necessary as traditional service structures face pressure. WordPress agencies traditionally operated on project-based or retainer models focused on implementation and maintenance. As AI handles routine implementation, successful firms shift toward strategic advisory roles, combining technical implementation with business strategy, compliance guidance, and performance optimization. Some agencies have developed “AI-augmented teams” where human experts supervise multiple AI agents, dramatically increasing productivity while maintaining quality control through human oversight. This model allows agencies to handle larger volumes of work while focusing human expertise on high-value activities like strategy, customization, and complex problem-solving.

The transformation extends to client relationships and service packaging. Rather than selling WordPress development as a standalone service, successful firms bundle technical implementation with ongoing optimization, compliance monitoring, and strategic consultation. They position themselves as industry partners rather than technical vendors, embedding deeply within client organizations to understand business challenges beyond website needs. This approach creates switching costs and relationship depth that pure AI solutions cannot replicate.

Investment priorities shift accordingly. Rather than focusing solely on technical training or tool acquisition, organizations allocate resources toward industry certifications, compliance expertise, and vertical-specific knowledge development. They establish partnerships with industry consultants, attend sector-specific conferences, and develop deep understanding of regulatory landscapes. Marketing strategies evolve from emphasizing technical capabilities to showcasing industry expertise and business outcomes.

The evidence points toward adaptive specialization as the sustainable path forward—deep, multi-domain expertise combined with systematic learning capabilities, network connections, and organizational support structures that enable continuous evolution. Organizations that recognize this shift can proactively restructure their operations, moving from horizontal technical services to vertical industry solutions. They can develop new revenue models that capture value from expertise rather than execution, establish partnerships that provide domain knowledge, and create internal cultures that reward continuous learning and adaptation.

This transformation acknowledges that in a world where AI handles routine knowledge work, sustainable value emerges at the intersections where multiple specialized domains meet, where human judgment navigates complexity that algorithms cannot map, where experience provides insights beyond pattern matching. The organizations and individuals who thrive will be those who build adaptive capacity into their business models and specialization strategies from the beginning, creating resilient structures that evolve with technological change rather than being disrupted by it.

Choosing your edge

Margaret Patterson understood something fundamental that March morning in 1979, something that transcends the specific technology that displaced her. She grasped the essential truth: when everyone can do the work, value migrates to understanding what the work means.

The punch card operators who thought their jobs were secure because “someone has to input the data” mirror today’s knowledge workers who believe their roles are safe because “someone has to write the content” or “someone has to code the website” or “someone has to analyze the data.”

They’re right, of course. Someone does have to do these things. But increasingly, that someone is anyone with an AI assistant.

Her story reminds us that technological displacement follows predictable patterns, but it also teaches us something more profound: those who survive and thrive aren’t necessarily the most skilled at the old way of working. They’re the ones who recognize the shift early and position themselves where the new technology cannot reach.

The punch card operators who successfully transitioned didn’t try to punch cards faster or more accurately—that race was already lost. Instead, they moved into database design, systems analysis, data architecture. They shifted from executing tasks to understanding systems.

So, the path forward isn’t mysterious—it’s a mathematical certainty. LLMs operate at the center of knowledge distributions. Value accumulates at the edges. The only sustainable strategy is to move toward those edges, to specialize so deeply that you operate beyond the reach of statistical averaging.

The only question that remains is: which edge will you choose?

References

Acemoglu, D., & Restrepo, P. (2024). Artificial intelligence and labor market polarization: Cross-national evidence. Journal of Labour Economics, 42(3), 567-598.

Autor, D. H., Katz, L. F., & Kearney, M. S. (2006). The polarization of the U.S. labor market. American Economic Review, 96(2), 189-194.

Autor, D. H., Mindell, D., & Reynolds, E. (2025). The cascade effect: AI deployment and accelerating labor market disruption. Harvard Kennedy School Working Paper Series. Retrieved from https://www.hks.harvard.edu/publications/cascade-effect-ai-labor-markets

Borland, J., & Coelli, M. (2023). Worker specialization and the consequences of occupational decline. Institute for Fiscal Studies in Norway (IFAU) Working Paper 2025-7. Retrieved from https://www.ifau.se/globalassets/pdf/se/2025/wp-2025-7-worker-specialization-and-the-consequences-of-occupational-decline.pdf

Brookings Institution. (2024). Rising inequality: A major issue of our time. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/articles/rising-inequality-a-major-issue-of-our-time/

Climate EC. (2020). Climate change and employment in the EU. European Commission Climate Action. Retrieved from https://climate.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2016-11/climate_change_employment_eu_en.pdf

Deming, D., & Summers, L. (2025). Is AI already shaking up the labor market? Harvard Gazette. Retrieved from https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2025/02/is-ai-already-shaking-up-labor-market-a-i-artificial-intelligence/

Deming, D. J., Ong, C., & Summers, L. H. (2025). Technological Disruption in the Labor Market (NBER Working Paper No. 33323). National Bureau of Economic Research. http://www.nber.org/papers/w33323

Fonseca, T., Lima, F., & Pereira, S. C. (2018). Job polarization, technological change and routinization: Evidence for Portugal. IZA Conference Paper. Retrieved from https://conference.iza.org/conference_files/Statistic_2018/fonseca_t26349.pdf

Fonseca, T., Lima, F., & Pereira, S. C. (2025). The impact of specialization on IT workers: Evidence from the dotcom boom and bust. Journal of Economics and Statistics. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0927537125001095

Goos, M., Manning, A., & Salomons, A. (2009). Job polarization in Europe. American Economic Review, 99(2), 58-63.

Hemingway, E. (1926). The sun also rises. Scribner.

HubSpot. (2024). The state of AI in marketing 2024. HubSpot Research Report. Retrieved from https://www.hubspot.com/state-of-ai-marketing

International Monetary Fund. (2024). AI will transform the global economy: Let’s make sure it benefits humanity. Retrieved from https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2024/01/14/ai-will-transform-the-global-economy-lets-make-sure-it-benefits-humanity

International Monetary Fund. (2025). The impact of artificial intelligence on income inequality. IMF Working Paper. Retrieved from https://www.elibrary.imf.org/view/journals/001/2025/068/article-A001-en.xml

Israilidis, J., & Antoniou, A. (2022). Knowledge management failures in aerospace and defense industries. White Rose Research Repository. Retrieved from https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/id/eprint/193240/7/1369471_Israilidis_Antoniou.pdf

Kansas City Regional Council. (2022). Technology industry employment analysis for Greater Kansas City. Mid-America Regional Council. Retrieved from https://www.marc.org/sites/default/files/2022-05/Technology-TIE.pdf

Li, R., & Chen, M. (2021). Worker adaptation during organizational transformation: A COVID-19 natural experiment. University of Hawaii Scholar Space. Retrieved from https://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/bitstreams/baef4bb0-eff8-4f3b-9666-7889f82e0d7a/download

Microsoft. (2024). Work Trend Index: AI at work is here. Microsoft Workforce Analysis Report. Retrieved from https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/worklab/work-trend-index/ai-at-work-is-here

Microsoft Research. (2024). The impact of AI on web development professions. Microsoft Technical Report.

National Center for Biotechnology Information. (2021). Healthcare worker adaptation strategies during organizational change. PMC Articles, PMC8325788. Retrieved from https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8325788/

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2024a). Artificial intelligence and wage inequality. Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2024/04/artificial-intelligence-and-wage-inequality_563908cc/bf98a45c-en.pdf

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2024b). Labour market polarization in advanced countries. Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/labour-market-polarization-in-advanced-countries_06804863-en.html

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2024c). What impact has AI had on wage inequality? Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2024/11/what-impact-has-ai-had-on-wage-inequality_8943dfe0/7fb21f59-en.pdf

Regional Australia Institute. (2024). The impacts of specialization and diversification on Australia’s mid-sized towns. Retrieved from https://www.regionalaustralia.org.au/common/Uploaded%20files/Files/2024/Backdated%20ISIP%20Reports/The%20impacts%20of%20specialization%20and%20diversification%20on%20Australia’s%20mid-sized%20towns.pdf

Sciences Po Department of Economics. (2025). Two faces of worker specialization. Sciences Po Working Papers. Retrieved from https://www.sciencespo.fr/department-economics/files/2025_barany_and_holzheu_two_faces_of_worker_specialization_v3.pdf

Search Engine Journal. (2024). SEO professionals and AI adoption: Industry survey results. Retrieved from https://www.searchenginejournal.com/seo-ai-adoption-survey

Singh, P., & Kumar, A. (2017). Multi-specialization as an adaptation strategy in the knowledge economy. Science Direct, 217(3), 186-203. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S221446251730186X

Smith, A. (1776). An inquiry into the nature and causes of the wealth of nations. London: W. Strahan and T. Cadell.

University of Minnesota Libraries. (2018). The power of the punch card. Library News & Events. Retrieved from https://libnews.umn.edu/2018/11/power-of-the-punch-card/

World Bank. (2020). Labor market polarization in developing countries: Challenges ahead. World Bank Development Talk. Retrieved from https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/developmenttalk/labor-market-polarization-developing-countries-challenges-ahead

World Inequality Database. (2022). World inequality report 2022. Retrieved from https://wir2022.wid.world/chapter-2/